Did you know that Japan has an Indigenous population? They are the Ainu.

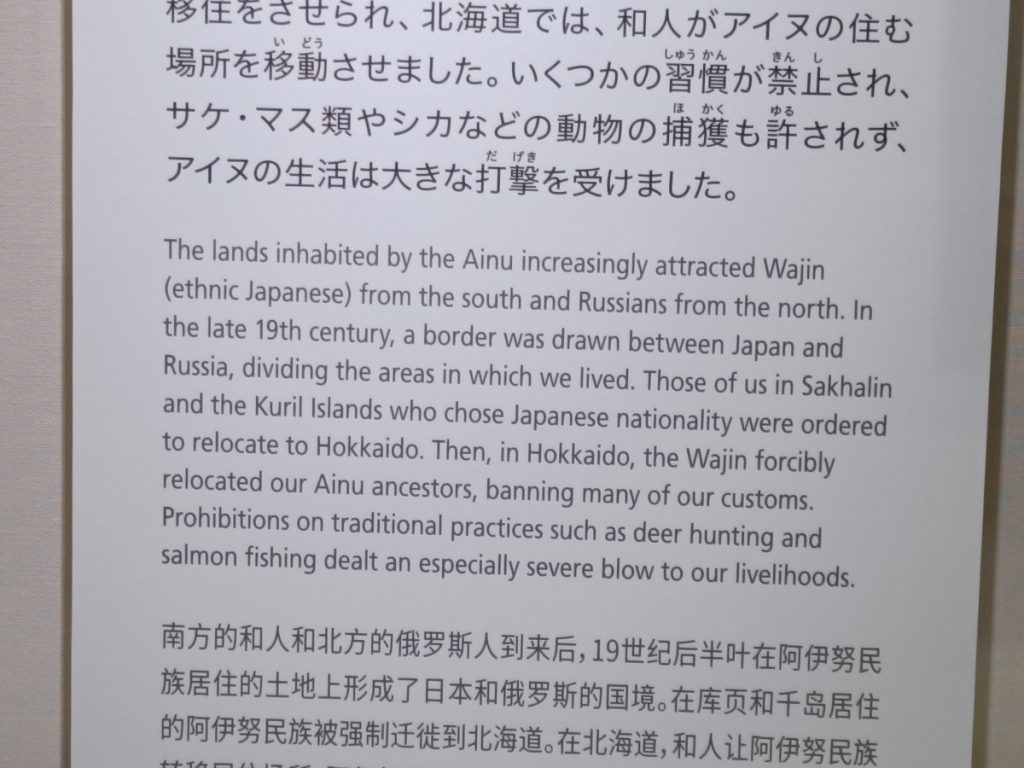

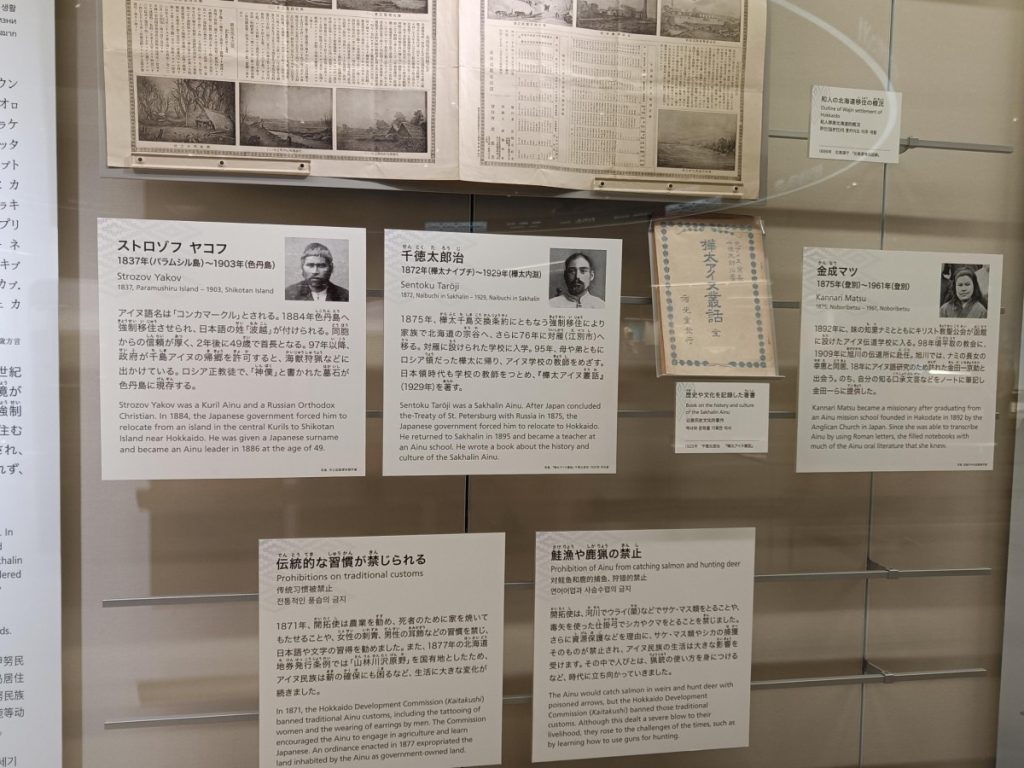

We visited Upopoy, the National Ainu Museum & Park, today. The Ainu people are the Indigenous people of Japan (specifically Hokkaido), and much like other Indigenous peoples, they’ve suffered oppression and colonisation. Language, culture, knowledge, and spirituality were all in danger of being purposefully destroyed and lost.

On my last trip to Sapporo, I visited the Ainu Cultural Exchange Centre (Sapporo Pirika Kotan), so I had some idea of the scope of living Ainu culture in Japan.

This new centre is a way forward, with the Ainu as leaders and support from the Japanese government.

Built in 2020, in Shiraoi, Upoypoy is 1.5 hours out of Sapporo by train.

It’s hard to get to, but in some ways, more appropriate as it’s a park reserve and a living cultural centre and museum. You have to go on a bit of a journey…

Getting to Shiraoi

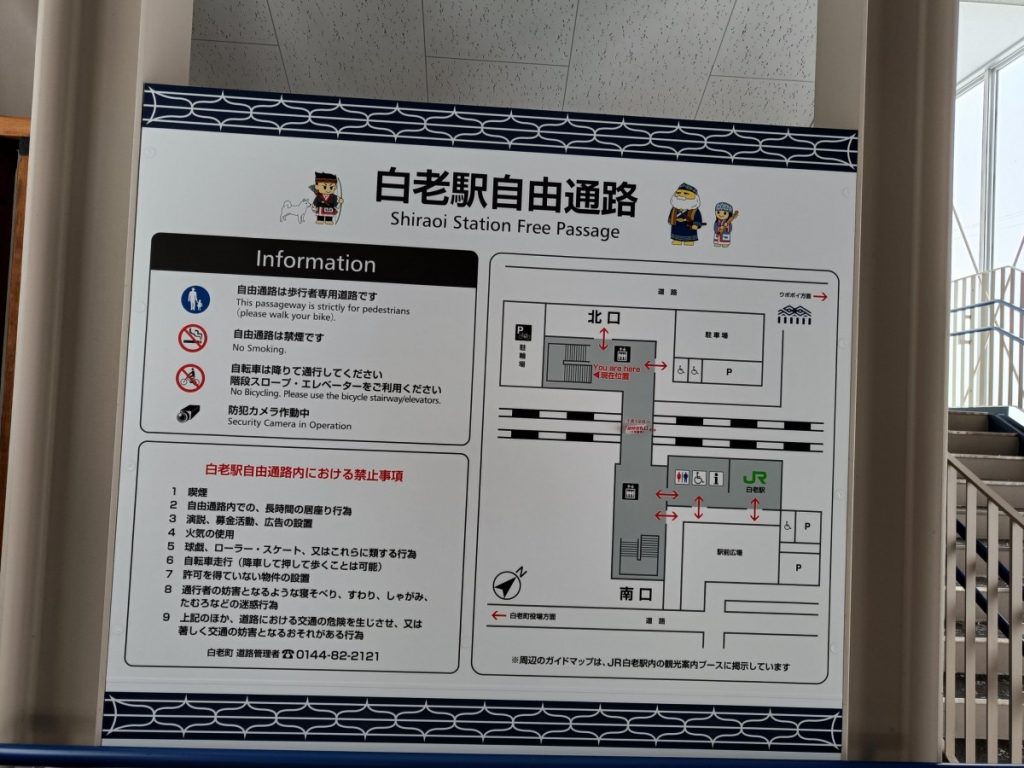

From Shin-Sapporo station, take the Hokuto Limited Express to Shiraoi station. The journey takes about 1 hour. From there, it’s a 5-minute walk to Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park.

We arrived with luggage but the train station has plenty of paid lockers to store your bags. Max 700 yen for the biggest lockers.

Lockers at Shiraoi station. Apparently, it gets very busy in Summer, but looks like it’s empty in Winter.

Walkway from the station across the railway tracks to the main road to Upopoy. Much needed in the heavy snow.

What is Upopoy?

From the website: “Upopoy serves as a national center for the revival of Ainu culture.”

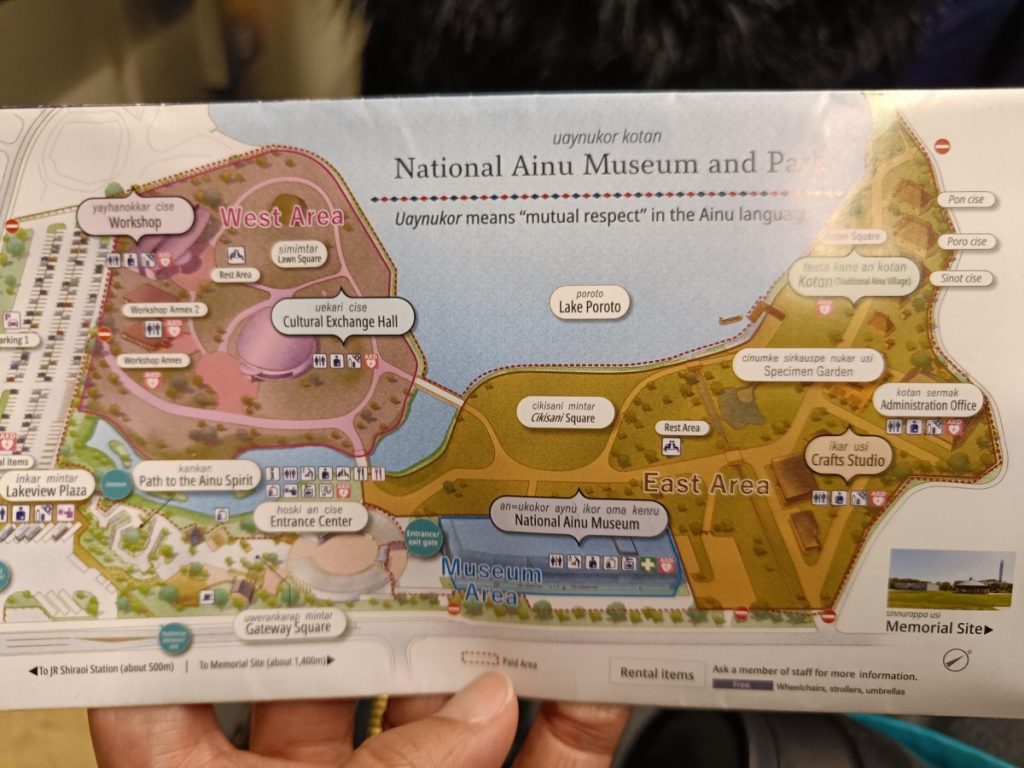

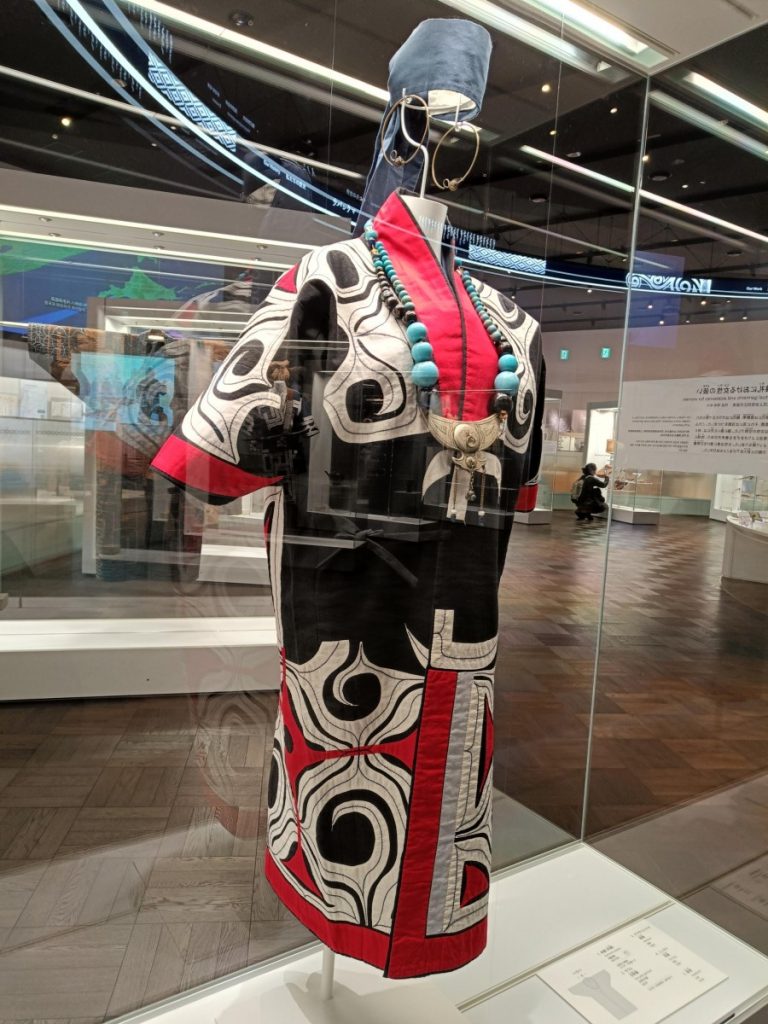

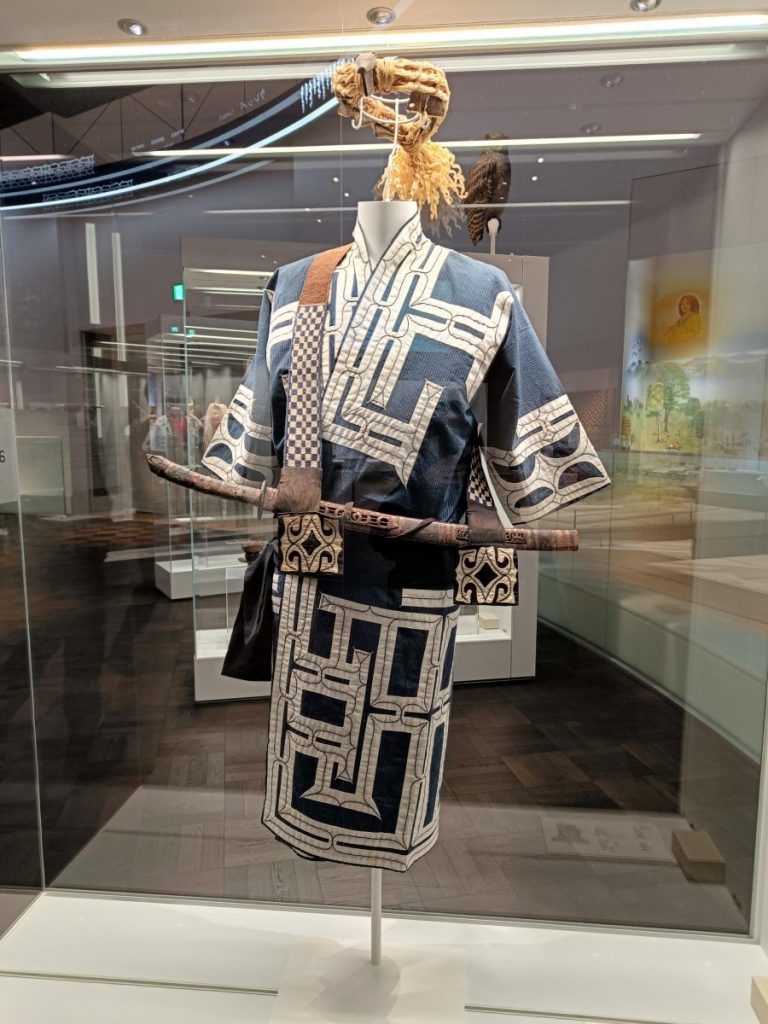

As well as a museum, Upopoy also covers a village, a memorial (where the reclaimed remains of Ainu from museums around the world are returned home and honoured), a cultural exchange centre (performances) and a workshop (musical instruments, cooking, art, talks) educating local Japanese and foreigners.

It is not a museum of relics, but a conscious attempt by the Japanese government to assist the Ainu in reviving and preserving their culture. There are many complexities to this, and there are questions and criticisms from Ainu living in Japan on the broader social impact and awareness beyond a center in a town a few hours out of a major city. I do not have the knowledge to comment on this, and I defer to the Ainu people for their opinion on Upopoy and their lived experience. This article from the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) shares some of these questions and criticisms.

What I can attempt is to explain how I saw this cultural center as an Australian tourist, viewing this through the lense of the atrocities and oppressions that Indigenous Australians suffered. We have our own history to acknowledge in Australia and Upopoy, despite its imperfections, offers an insight on how to start and what to learn.

Facilities and Buildings at Upopoy

The experience

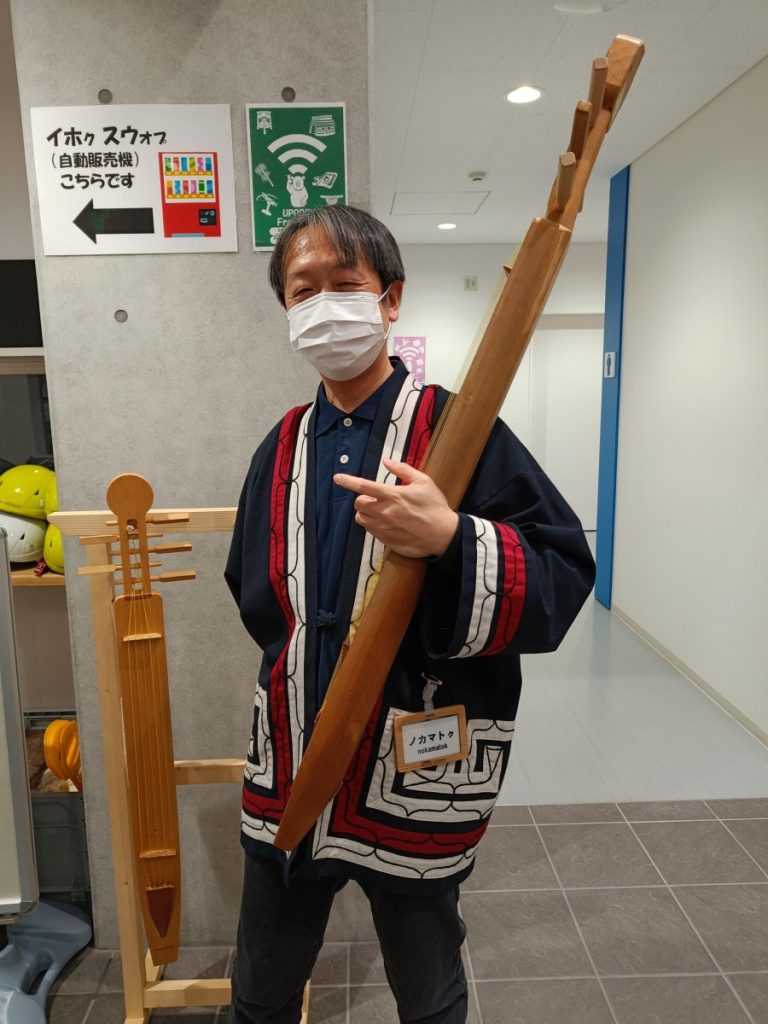

The Ainu staff/teachers, like Nokamatok, the mukkuri and tonkori (musical instruments) teacher, were friendly and eager to share their culture. While we were there, a group of Maori attended the performance as important guests.

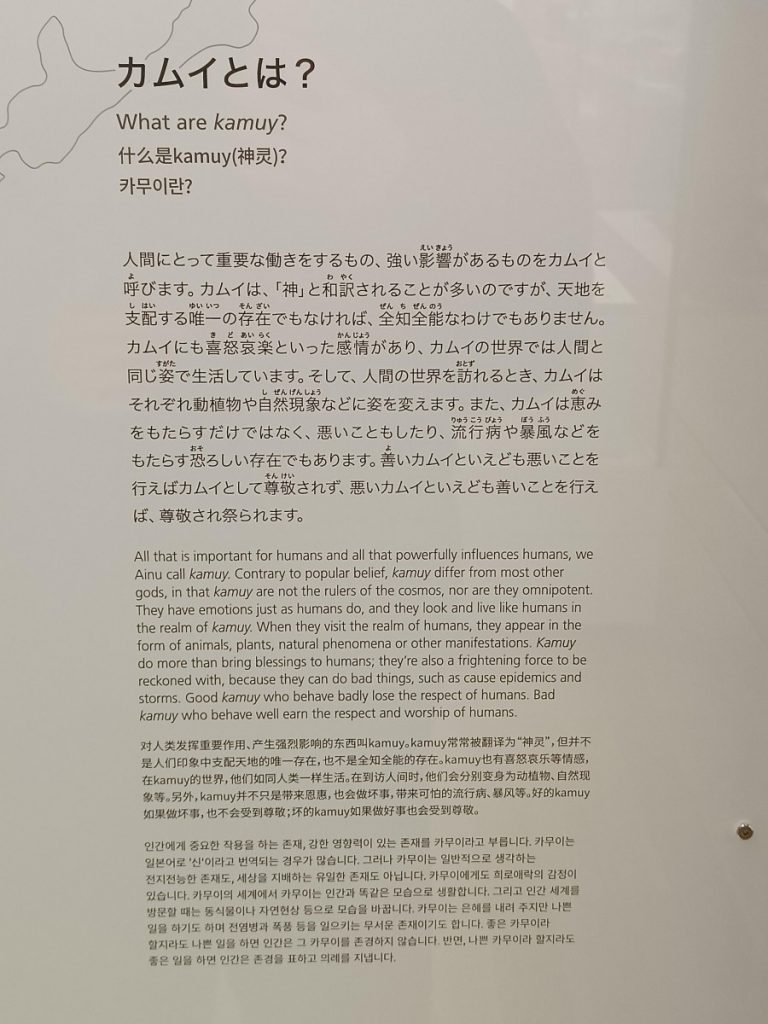

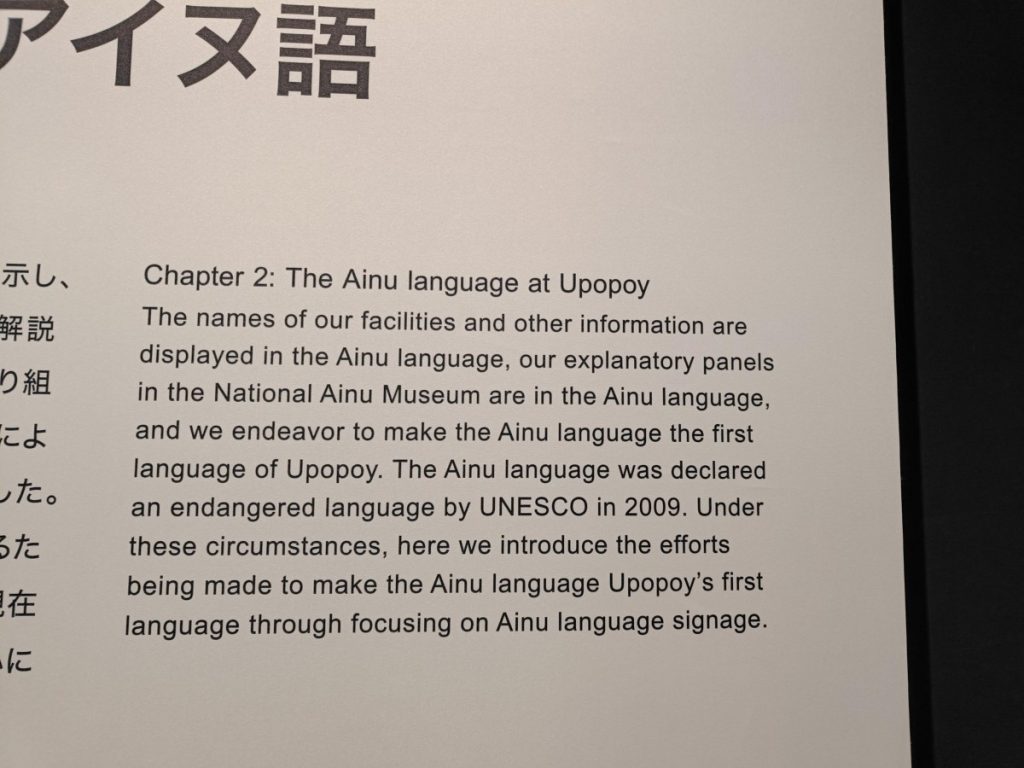

What I especially liked about this museum is that it is narrated BY the Ainu. The museum info isn’t in the third-person, it’s in the first-person. Usually, a museum will speak in anthropological terms like “The Xxx people are….they…. them…” And usually discuss in past-tense, as museums generally hold and exhibit “old” things.

But in this museum, the “narrator’s voice” is the Ainu. The info says “We, the Ainu…We… Our…Us ..” Reinforcing a living voice and culture.

Language really matters and in this case, it brings the reader into the present, and “face-to-face” so to speak, with the Ainu narrator, humanising the experience. We aren’t just reading about an artifact, we are in conversation with a people.

If felt like the Ainu are not just performers at Upopoy, the are the writers, decision-makers, narrators, staff, curators, managers and main characters. They’re leaders. As they should be.

This place is educating many about the history of Ainu and Japan. From one identity, the other is defined and so on and so forth, as both cultures now exist in the same location, with a shared history of colonial and Indigenous, oppressor and advocate, survivor and bystander…

Video installation in the permanent exhibition. No video allowed and we respected that. Visitors are invited to sit around a hearth and listen to the oral traditions and stories.

As we watched, we Australians couldn’t help but wonder what and how our Aboriginal and broader Australian cultural identity would be merged if we had this kind of education back home.

As the 26th of January approaches, Upopoy’s existence and the Ainu’s resilient revival offers us a glimpse of how we can transform and heal. Because a holiday to mark an invasion is not it.